July 2010

Philip Gatward's images document the South Omo indigenous tribes...

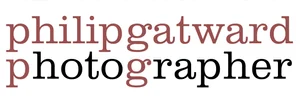

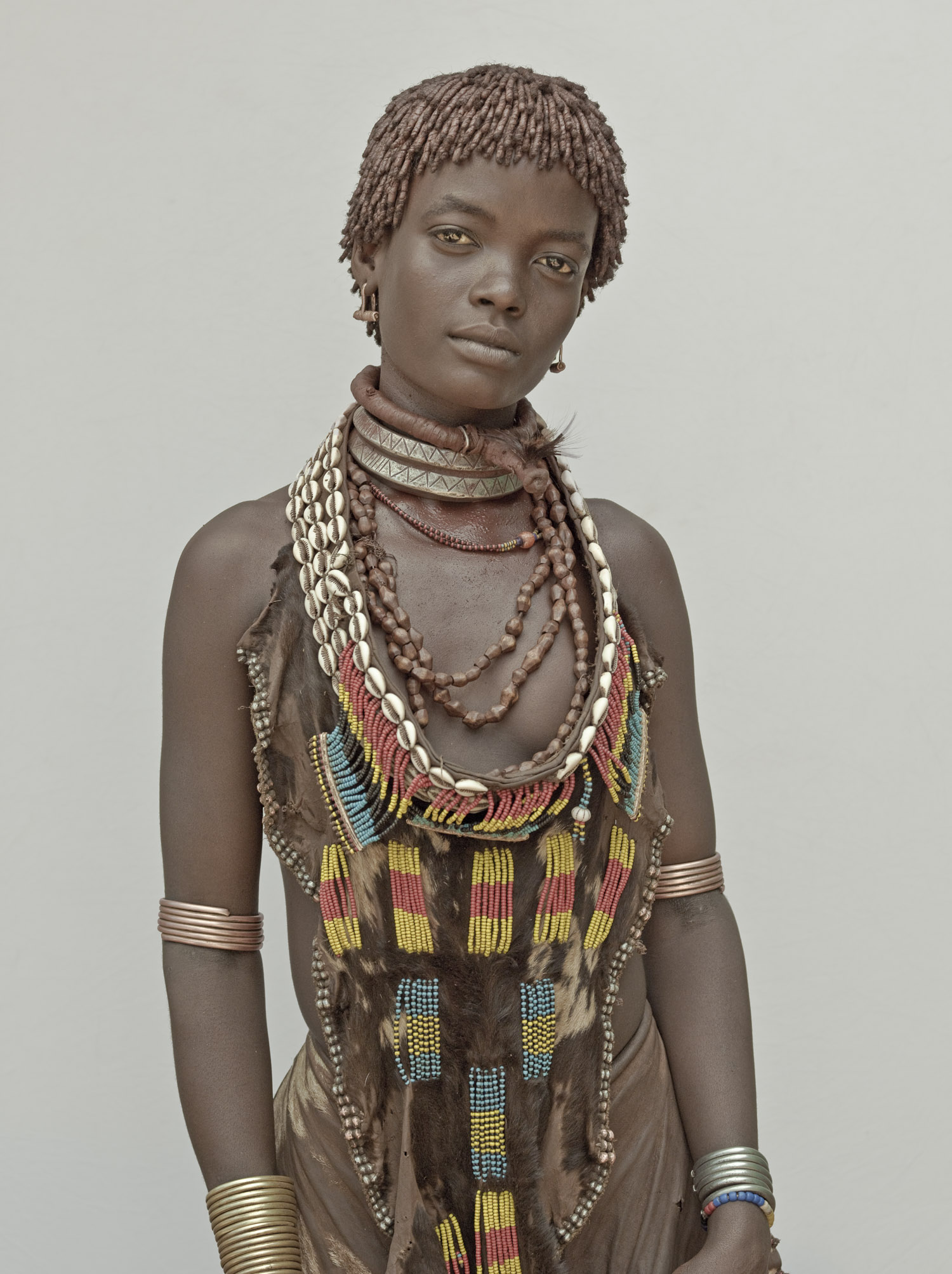

From pedigree to portraiture: Ethnographs is a new exhibition coming to Art Work Space in London this month, which will house photographer Philip Gatward’s images from his time spent documenting the striking indigenous tribes living in the South Omo Valley region in Ethiopia. The exhibition comes as a new direction for Gatward, whose award winning work has encompassed capturing a range of subjects, from delicate flowers to the fantastic aesthetics of the animal world. Ethnographs remains true to Gatward’s distinctive style, producing a series of honest photographs which beautifully demonstrate the culture and aesthetics of the tribe in a thoroughly non-pretentious and organic manner. Dazed went to find out more about this extraordinary project...

Dazed Digital: How did the idea for the exhibition crystalise in your mind? What steps did you take to realise it?

Philip Gatward: I visualise the pictures long before I shoot them. To capture and manipulate the images is just a procedure, good or bad, that I have to go through to present the work. Each project is part of a bigger puzzle that I feel first, then endeavour to capture. That puzzle is taking shape and beginning to make more sense to me with every project I complete - the comfort of childhood memories are revealing themselves in the puzzle.

DD: You have stated that Robert Gardner’s documentary Rivers of Sand played a large part in influencing your decision to shoot this series of photographs. Could you tell me a little bit about this influence?

Philip Gatward: I have not seen the documentary since childhood, but the visuals from the film have stayed with me throughout my life. And my fascination with the idea of complex, cohesive societies that are utterly unlike our own has also not diminished in any way.

DD: The collection seems to concentrate on the wonderfully unique appearance of the tribe. Why did you not choose to also document and expose social inequality and male supremacy as Gardner does is in his documentary?

Philip Gatward: With Ethnographs, I wanted to expose the codes and projections of our own society, and I wanted to start the project with a neutral viewpoint. This was my first trip to Africa and I went with an open mind, so I felt that I would have been foolish to impinge my moral and social codes by documenting theirs. Living in East London I see poverty, malnutrition and male supremacy every day and it made me want to turn my camera on our society on my return. I’m not an overtly political artist...yet.

DD: You have previously worked for huge corporate companies such as Nike, Coca Cola, Conde Nast and Cadbury. What is the relationship, for you, between this work and Ethnographs? Was it a conscious decision to move away from the western wealth of advertising?

Philip Gatward: It was a conscious decision to move away from the cult of celebrity. Are real people not enough? In the past, advertising photography has been the ideal place for me to perfect my skills and ideas. It’s where I realised that I pre-visualise everything in order to get the shots - and of course photography isn’t cheap. I can bring the things I have learnt through shooting ads to bear on my art and now I have the facilities to do it.

DD: You lived with the tribe for six weeks – did you form any special bonds with any of your subjects?

Philip Gatward: Yes, Bali, a young guy from the Hamer tribe. He didn’t speak English and, at first, we would chat through a translator. But we just clicked, and even when the translator wasn’t there, the bond wasn’t diminished. We laughed a lot and it didn’t feel any different to sitting in the pub with a mate, except we were sitting round the campfire in the pitch black, drinking tej. However, I decided that the subjects of Ethnographs should not be named because I didn’t want to establish that relationship between interloper, photographer and subject; I wanted to remove my relationship from the equation.

DD: How did you approach the tribe? Were the subjects open about being photographed?

Philip Gatward: Through Bali and our guides I directed the poses. They were very self-aware; very knowing about how good they looked and comfortable with themselves - unlike us. There was real excitement in the villages about being photographed, and the shoots were fun, with lots of laughter.

DD: Was there anyone in particular in the tribe that you enjoyed photographing? Were there any stories that were revealed throughout the time you spent there?

Philip Gatward: It’s hard to pick just one. One of the subjects, Teshome, became a friend. He was someone who had returned from modern city life to live among the tribes, in a nearby village. He had a hard life, struggled to find enough work and chewed a bit too much chaat, but was surrounded by friends among the tribes people. He had a sponsor at one point, a Westerner who was putting him through university, but who was killed in a helicopter crash just as Teshome was getting his life together.

DD: Portraiture is something you have concentrated on in your work, is there any other branch of art or photography you would be interested in producing?

Philip Gatward: I don’t see myself necessarily as a portraitist. As the digital form has taken hold I find myself looking to explore much simpler, un-manufactured imagery.

DD: What is next for you? Do you have any other projects in the pipeline?

Philip Gatward: Leaping pigs.